A Testimonial Collage

By Jack Saul

April 7, 2013

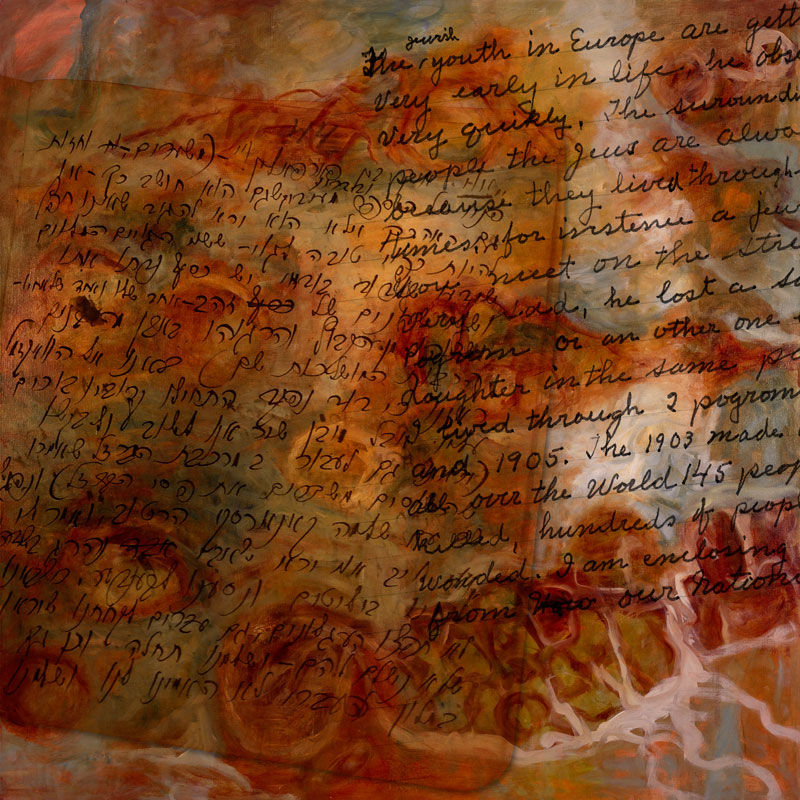

Through painting I rediscovered memories of Kishinev that I had carried during my life – including my grandfather’s story of the pogroms he witnessed as a child in 1903 and 1905. He wrote in a letter to me in the spring of 1981:

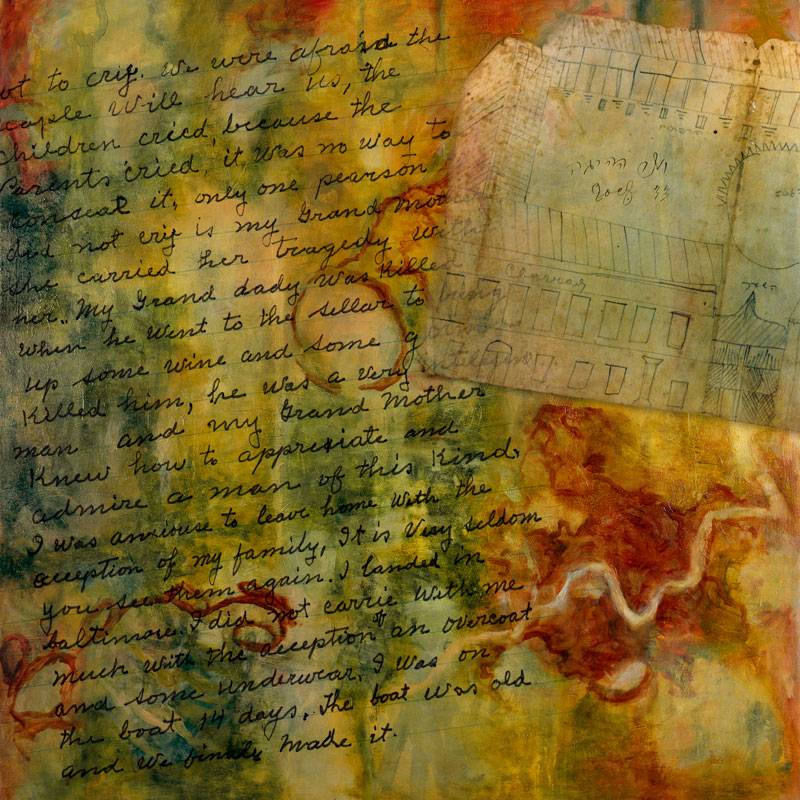

“We huddled together in a corner of the house and we tried for the children not to cry. We were afraid the people will hear us, the children cried because the parents cried. There was no way to conceal it. Only one person did not cry, my Grandmother. She carried her tragedy with her. My granddaddy was killed when he went to the cellar to bring up some wine, and some goyim killed him. He was a very intelligent man and my Grandmother knew how to appreciate and admire a man of this kind.”

Whether my grandfather’s grandfather was killed during the Passover Seder disrupted by the pogrom of 1903 or some previous religious ceremony, I can’t help but thinking about the family Seders my grandfather proudly led each year. What must he have privately remembered about that tragic holiday from his childhood as he stood before his children and grandchildren in Atlanta, Georgia singing the Sheur Ashurim, the Song of Songs from the Passover Haggada?

My grandfather was a man of few words. He chose to defer to poets, such as Emerson to convey the beauty of spring and to the poet he most admired, Chaim Nachman Bialik to express the plight of the Jews. Accompanying the letter he wrote to me about pogroms in Kishinev and his emigration to the United States, was a poem by Bailik entitled “Israel’s Strength,” which he had torn from the Martyrology section of the High Holiday Prayer book.

Chayim Nachman Bialik, an esteemed leader and poet in the Jewish world at the time was chosen to head a team sent from Odessa to document the deaths, injuries and destruction that resulted from the 1903 Kishinev pogrom. This event was particularly shocking because of the degree of barbarity displayed by the unruly crowd, which included the butchering of children and infants and raping of women. Forty-nine Jews were killed and hundreds were injured. Over 2000 were left homeless. The pogrom had been provoked by the local newspapers, condoned by the church and permitted by the police. It was a national humiliation for the Jewish people and revealed how vulnerable they were, relying on the protection from their host countries.

Last month, I visited Beit Bialik in Tel Aviv, the former home of Bialik – now museum, and was kindly granted permission to view the journals that Bialik kept during his visit to Kishinev. He wrote hundreds of pages documenting each casualty, together with numerous interviews of witnesses, and a drawing of the courtyard where many of the killings took place. Rather than publish a factual account of the massacre, Bialik instead wrote his epic poem, The City of Killings, in which he expresses his anger toward the Jews for their passivity and toward their God who was as poor and bankrupt as they. The poem was both a call to the Jews to defend themselves and to leave Europe. It also foreshadowed the genocidal fury to come during the 1918 Russian civil war and the Holocaust.

The two testimonial collages blend my paintings, my grandfather’s letters and the Kishinev journal entries and drawings of Bialik, courtesy of Beit Bialik archive.

*

To read further, click here >

Un colaj Testimonial

de Jack Saul

7 Aprilie, 2013

Picturile m-au ajutat să redescopăr Chișinăul din aminitirile mele de o viață - împreună cu poveștile din copilaria bunicului despre pogromurile la care a fost martor în 1903 și 1905. În primavara lui 1981 mi-a scris o scrisoare:

"Ne înghesuiam într-un colț al casei și încercam să oprim copiii din plâns. Ne temeam că oamenii ne vor auzi, copii plângeau pentru că părinții plângeau. Era greu de ascuns. O singură persoană nu a plâns. Bunica. Era una cu tragedia. Bunicul a fost ucis când s-a dus in pivniță să aducă ceva vin și un goim oarecare l-a omorât. A fost un om foarte deștept, iar bunica știa să aprecieze și să admire oameni ca el."

Chiar dacă bunicul bunicului a fost omorât în timpul Seder-ului de Passover, întrerupt de pogromul din 1903 sau poate mai devreme, în cursul unor ceremonii religioase, nu pot să nu mă gândesc la Seder-urile de familie pe care bunicul le conducea cu mândrie în fiecare an. Oare ce aminitiri profund personale despre acea Sărbătoare tragică din copilărie îi veneau in minte în timp ce cânta în Atlanta, Georgia, în fața copiilor si nepoților Sheum Ashurim, Cântecul Cântecelor din Haggada de Pesah.

Bunicul nu vorbea mult. Prefera poeziile, ca cele ale lui Emerson, pentru a exprima frumusețea primăverii, sau ca cele ale poetului lui preferat Chaim Nachman Bialik pentru a evoca soarta evreilor. Scrisoarea pe care mi-a scris-o despre Chișinău, despre pogroame și emigrarea in Statele Unite, avea atașată o pagină cu un poem de Bialik intitulat "Puterea Israelului", pe care el o rupsese din capitolul Martirologie din Cartea de Rugăciuni pentru Înaltele Sărbători (?)

Chaim Nachman Bialik, un leader respectat al Comunității Evreiești din acea vreme, a fost numit (ales?) să conducă o echipă din Odessa, pentru a culege dovezi și documente despre omorurile, crimele, și distrugerile pogromului din 1903 la Chișinău, cunoscut pentru cruzimea deosebită a mulțimii dezlănțuite, cu copii si bebeluși măcelariți, și femei violate. Patruzeci si nouă de Evrei au fost omorâți, sute și sute au fost răniți, peste 2000 au rămas fără adăpost. Pogromul a fost provocat de un ziar local, cu susținerea tacită a Bisericii, și cu aprobarea Poliției. A fost o umilire natională a Evreilor, o dovadă a vulnerabilității lor, chiar si atunci cand sunt sub protecția Statelor in care trăiesc.

Luna trecută am vizitat Beit Bialik - fosta casă a lui Bialik - acum muzeu, și mi s-a permis, cu amabilitate, să văd jurnalele lui Bialik din timpul vizitei la Chișinău. A scris sute de pagini și a strâns dovezi despre fiecare victimă, inclusiv numeroase interviuri ale martorilor oculari ai pogromului, a inclus până și o schiță a curții în care s-au produs multe omoruri. În loc să publice un raport secvențial al faptelor, Bialik a scris, în schimb, un poem epic, Orașul Omorurilor, în care iși exprimă dezaprobarea și mânia împotriva evreilor, pentru pasivitatea lor, precum și împotriva lui Dumnezeu, care a fost la fel de sărac și (falit?) ca și ei. Poemul a fost o chemare pentru autoapărare a Evreilor și un apel pentru emigrarea din Europa. Poemul, de asemenea, a prevăzut (?) furia genocidă ce avea sa urmeze - mai intâi, în războiul civil din 1918 din Rusia, urmată mai târziu de Holocaust.

--

Translated to Romanian by Michael Sipos

|